REITs are contributing a range of solutions to the affordable housing crisis by focusing on median-priced apartments, manufactured homes, or partnering with nonprofits.

Stagnant wage growth coupled with increased housing costs and a shortage of affordable homes for renters and buyers have created a housing crisis in the U.S. The COVID-19 pandemic and global recession have further widened the gap between wages and housing costs, making the role that REITs play in supplying affordable, middle-income housing more important than ever.

In addition to supplying a vital social need, REITs have also tapped a market niche that provides consistent and solid returns for their investors, even during the current period of economic uncertainty.

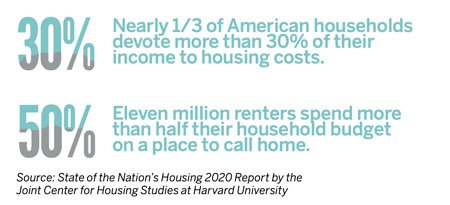

According to the State of the Nation’s Housing 2020 Report by the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University, approximately 37.1 million households, about 30% of all American households, were considered “cost burdened” in 2019, which means they spent more than 30% of their income on housing. Approximately 14% of American households spend 50% or more of their income on housing, the report states.

The problem is worse for extremely low-income renters whose household income is below the poverty level, or 30% of area median income. According to the National Low Income Housing Coalition, the U.S. has a shortage of seven million affordable rental homes for those households.

Christopher Ptomey, executive director of the Terwilliger Center for Housing at the Urban Land Institute, says there’s a disconnect in the housing market between the higher end of the market and the low end.

“The problem is there’s no moderate-income housing for people to move up from lower-cost housing, or to move down from an expensive apartment if their circumstances change. REITs can provide investment into that middle level of housing,” Ptomey says.

While many people associate affordable housing with low-income households, financial experts generally define “affordable” as a home that costs less than 30% of household income.

“The most common role for REITs to play in creating more affordable housing options is by purchasing and upgrading older multifamily buildings,” says Merrill Ross, managing director and senior research analyst for REITs with Compass Point Research and Trading. She says this strategy, which benefits investors looking for reliable growth, works best in markets with good job growth for middle-income jobs, such as Texas, Florida, and South Carolina.

Affordable Options

Mark Decker, Jr., president and CEO of Centerspace Homes (formerly IRET) (NYSE: CSR), says his company’s strategy shifted about three years ago from several property sectors to just one: multifamily housing in secondary and tertiary markets in the Midwest.

“We’re focused on the fat part of the demand curve—apartments that are affordable to most people in the market,” Decker says. “If you think of the housing market as a bell curve, we’re invested a little to the left of the peak of the curve and a lot to the right. We’re trying to make money for our investors, so we put ourselves in a position where there’s lots of demand and pricing power.”

At the same time, rents remain attainable for median-income households. For example, the average rent in Centerspace’s Minneapolis portfolio is $1,500 to $1,600—slightly above the average rent of $1,400 in that market.

“We’re ‘freshwater fishermen’, not likely to go into the coastal markets,” Decker says. “We focus on innovative markets with a high quality of life like Denver and the Twin Cities and Billings, Montana, which is a smaller market but one that’s attracting new residents.”

Decker says that REITs have a role to play in solving the affordable housing crisis.

“We’re not telling investors that we’re trying to build affordable housing, because that’s not our business,” says Decker. “But there’s a solution between ‘profits are everything’ versus ‘the government subsidizes everything’. We’re just trying to make our corner as good as possible and invest in locations where we can buy and improve housing that’s affordable for most of the people who live there.”

Brian Mitts, CFO of NexPoint Real Estate Advisors, a real estate investment platform that includes NexPoint Residential Trust, Inc. (NYSE: NXRT), says “the simplest way we define affordable housing is by looking at the demographics of our tenant and the market.” The average household income of NexPoint tenants is about $55,000 and rents typically require 20% to 25% of their income, he says.

Mitts says that NexPoint’s strategy is simple: focus on growing Sun Belt markets and locations where other companies are not investing. “We go into older garden-style apartment communities that haven’t been invested in for 20 years, bring the apartments into the modern era, and continue to charge affordable rents,” Mitts says.

NexPoint buys these communities at a large discount and saves 30% or more compared to the land, labor, and materials costs of building a new community, Mitts explains. Depending on the condition of the community and the market, NexPoint will modernize the leasing center, pool, business center, and possibly the parking lot or roof if needed. The interiors of the units are updated on a natural basis when tenants move. Carpets are replaced with durable floors, cabinets are repainted, fixtures and hardware are replaced, and energy-efficient appliances are installed.

“If we spend $5,000 on a unit, we get a good return if we can charge $50 or $100 more in rent,” Mitts says. “We’re delivering value to renters and investors.”

When the pandemic hit, NexPoint developed payment plans for tenants who had lost income and helped connect others with $1 million in rental assistance from a variety of sources.

“Across our portfolio, we have maybe 2% at most of our tenants who owe back rent now,” Mitts says.

Adding Value

The low cost of living and low taxes in Texas have attracted businesses and therefore renters to the state, says John Bailey, CEO of BSR Real Estate Investment Trust (TSX: HOM.U; HOM.UN). Bailey says BSR plans to double the size of its portfolio in that state over the next three years. The Canadian-based REIT went public in May 2018.

“Our focus is on providing affordable homes to median-income households in the markets we serve,” Bailey says. The average ratio of rent to annual income across the BSR portfolio is 19.3%. The median income in its core markets is $60,000 to $70,000. Those locations also have some of the lowest unemployment rates in the nation, Bailey says.

“Our strategy is to stay in our lane,” Bailey says. “My parents started this company in 1956 and in 1991 we started primarily investing in apartments that we buy and hold for the long term. We love the median-income cohort because there’s strong demand in a good economy and there’s strong demand in a downturn from people moving down from high-cost rentals.”

BSR recently began purchasing new, partially-leased multifamily properties, which Bailey says are “higher-end to us.” For example, they purchased a building in Houston in the fourth quarter of 2020 that was 36% leased and is now 72% leased. Their portfolio went from an average age of 29 years in 2018 to an average age of 16 years in 2020.

“We’re committed to maintaining our average rent-to-income ratios in the low 20% range,” Bailey says. Occupancy rates in 2020 remained at about 95%, he says. “We didn’t get our usual rent growth of 3% to 5%, but we got 2% rent growth, even in 2020, because of adding value to our buildings,” he adds. “Our investors are satisfied because we’ve shown the safety of our product.”

“Attainable Housing”

Meanwhile, lingering, often negative images of trailer parks and old-fashioned metal mobile homes have created a stigma among local communities and zoning officials that has prevented the widespread adoption of a simple solution to the affordable housing crisis: manufactured homes.

“We build modern, energy-efficient homes with 1,000 square feet, three bedrooms, two bathrooms, a storage shed and a driveway where you can park two cars on 5,000-square-foot lots that rent for $750 per month,” says Sam Landy, president and CEO of UMH Properties, Inc. (NYSE: UMH). “We have a waiting list for these homes and even during the pandemic we had 97% occupancy rates and 98% rental payments.”

John McLaren, president and COO of Sun Communities, Inc. (NYSE: SUI), says manufactured housing “truly is the best value proposition for affordable housing.” He cites the lower barrier to entry—Sun’s average new home sale price last year was $135,000—along with lower taxes for a home that is situated in a highly-amenitized community. McLaren says Sun Communities likes to refer to its manufactured homes as “attainable housing.”

UMH, which was founded in 1968 by Landy’s father Eugene, became a REIT in 1985 and now has a portfolio of 126 manufactured home communities. “We went public because only a REIT could generate the equity and financial staying power to afford to invest in the land and the time it takes to overcome resistance to this affordable workforce housing,” Landy says.

The manufactured housing industry was booming between the 1960s and 1990s, Landy explains, when people would buy and finance their homes and rent their lot. “Unfortunately, many of those loans went bad in the early 2000s because of the loss of manufacturing jobs that meant people needed to relocate,” he says.

Many of the homes were abandoned, Landy notes. “After the housing crisis, our customers couldn’t get financing, so we provided it ourselves, but the lending rules got tighter and too many people couldn’t meet the debt-to-income ratios or they had a previous foreclosure.” In 2011, UMH began renting their manufactured homes and expanded their portfolio. Most of their communities include a mix of renters and buyers.

Local Resistance

Despite recent progress, community opposition to manufactured homes continues to be a challenge.

“Once local authorities see what we’re building, there’s less resistance,” says Aaron Potter, director of ESG for UMH. “We try to bring legislators directly into our communities so they can see how clean they are, with sidewalks, swimming pools, manicured lawns and cars parked in the right places.”

Developing a manufactured housing community includes updating sewer lines and other infrastructure that adds value to the entire area, Potter says, which is embraced in locations such as Tennessee, Ohio, and Western Pennsylvania. Other areas, such as New Jersey and Northeastern Pennsylvania, however, continue to resist manufactured housing, he adds.

McLaren at Sun Communities says an “interesting evolution” has taken place over the last several years. He meets with municipalities, city and town councils, and planning commissions to discuss the REIT’s planned developments, and “four years ago it was a more difficult conversation than it is today.”

Part of that change is because Sun has completed seven greenfield developments in the last three-and-a-half years, enabling officials to see the quality of home finishes, the awareness of environmental impact, and the innovation in home design, McLaren explains.

McLaren adds that Sun Communities puts a “tremendous amount of effort” into creating a residential feel for their communities, making it difficult to distinguish between neighborhoods of manufactured homes versus those of traditional single family homes.

And while some acceleration to zoning and entitlement procedures has occurred, it is still a “very challenging process” to go through, McLaren adds.

Looking ahead, McLaren sees no let-up in demand within the manufactured housing niche. “COVID and 2020 demonstrated the need, more than ever, for attainable housing,” McLaren says. Sun’s application counts are at their highest level ever, he adds, “and that need continues to grow.”

Social Impact and Solid Returns

The pandemic has undoubtedly had an outsize impact on low-to-moderate income tenants, which includes essential workers such as home health aides, grocery store employees, delivery drivers, as well as those in the hospitality and retail industries, says Anne McCulloch, CEO of Housing Partnership Equity Trust (HPET), which invests in apartments affordable to households with incomes between 50% and 80% of area median income.

“We run our apartments on very thin margins, so we manage them carefully and have significant operating reserves set aside because we know our residents are more vulnerable than those with higher incomes,” McCulloch says.

HPET was created by nonprofit housing providers who realized it was a gamechanger to tap into private capital, McCulloch explains. “The government can’t be enough to solve the need for workforce housing,” she says. “We acquire properties with our nonprofit partners, who are some of the largest regional and national nonprofits and are deeply connected to the communities where they operate.”

The deals are conservative, typically with a 20% down payment and 80% financed with a Freddie Mac or Fannie Mae loan to HPET, according to McCulloch.

“With our nonprofit partners we can take advantage of state and local tax abatements and subsidies for affordable housing to reduce our operating costs and to be competitive for properties,” she says.

The nonprofit partnerships also make HPET’s offer more appealing to local jurisdictions that share the mission of preserving and creating affordable workforce housing.

“HPET’s model of partnering with ground level housing partnerships to provide them with capital is working spectacularly well to increase the supply of low-income housing and to attract investors,” Christopher Ptomey, executive director of the Terwilliger Center for Housing at the Urban Land Institute, notes.

McCulloch says that 120,000 to 240,000 units of affordable housing are lost every year because they are obsolete or repositioned for higher income housing. HPET focuses on rehabbing apartments with modest, cost-effective upgrades that drive down operating costs and in turn, create a better community.

Investors may not see high double-digit returns, but affordable housing has relatively low risk or volatility, McCulloch says. “Investing in housing is the single most holistic way to make a social impact because housing sits at the intersection of every aspect of society where equity lags,” she says.

Housing is also an easily understood investment, McCulloch points out. “There are lots of other impact investment options available, but some of them may have losses,” she says. “People come to us first because they want to make a positive impact on their community, but then they realize this is a solid, low-risk investment.”