Robert L. Johnson discusses the personal philosophy that has enabled him to become a titan of business and a leader in the Black community.

With a lifetime of groundbreaking achievements behind him, Robert L. Johnson’s entrepreneurial mind continues to explore ways to expand opportunity for the Black community. His appetite to do more speaks to the breadth of his professional expertise and the inherent notion of service that he has carried throughout his career.

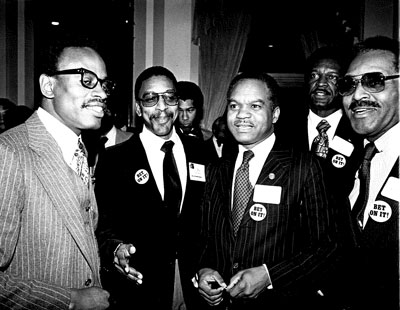

Johnson, founder and chairman of The RLJ Companies, LLC, which sponsored the formation of RLJ Lodging Trust (NYSE: RLJ), and the founder of Black Entertainment Television (BET), spoke with REIT magazine in an extended interview that explores, among other topics, the origins of his success, the impetus behind his business strategy, and how corporate America needs to tackle systemic racism.

This article has been adapted from that conversation. A longer podcast version of the interview is available, in addition to video excerpts focusing onREITs, race, and the pandemic.

At what point did you, the son of Edna and Archie, a teacher and a factory worker, and the ninth of 10 children, realize you were on the verge of being someone great?

I was the first of my siblings to go off to college, so that in itself was a milestone. The first to move to Washington, D.C., and get a career as a press secretary to a congressman and later on as a lobbyist for the National Cable Television Association.

All of these developments didn’t necessarily predict greatness, but they predicted that I had opportunities that my siblings didn’t have because of the change in times, the change in race relationships, the change in racial opportunities, the change in the political climate that caused the government to address civil rights and economic rights. It was more about coming of age at a time when the country was opening doors to Black Americans.

Looking back, what advice would you give to your younger self?

In anything you do, you’ve got to start off believing in yourself and that you’re delivering a service or a product to someone who is going to treat you fairly, respect you, and compensate you for what you’re doing.

That’s something that’s rooted in the idea that you have an obligation in society to care for yourself, your family, and others that are close to you. And at the same time, you have an obligation to live up to the tenets of society to make the whole community better.

When you launched BET in 1980, did you have any idea just how massive the impact on Black culture, and culture in general, would be?

I saw that the opportunity to create a media company targeting the viewing interest of Black Americans was something that was doable because it had already been done in print and radio. The great John Johnson, the founder of Ebony and Jet magazines, had already proved that Black Americans had a strong desire for targeted content. It did not exist in television because television was pretty much a medium that was distributed in local markets, except for the networks, which at the time BET started were principally only three: ABC, CBS, and NBC.

That programming was distributed to what they called a mass audience, and the mass of course were white consumers. There was no sense of niche programming until cable and satellite technology emerged, and out of that came networks like MTV, BET, CNN, ESPN, and CNN. BET was simply, in a technological way, an extension of Black print and radio.

You subsequently founded The RLJ Companies, LLC, with a portfolio that includes hotels, streaming channels, gaming, entertainment, fashion, car dealerships, 401(k) planning, and private equity. How does one have the mindset to build this type of empire?

You have to have a core belief in a vision to do something that at least you certainly haven’t done, and maybe in some cases in the Black community, that no one else has done.

When I looked at all these other businesses, I thought that there ought to be a role for Blacks in business and private equity. There were no Blacks in the hotel real estate business of any significance when I and my partner, Tom Baltimore (current CEO of Park Hotels & Resorts Inc. (NYSE: PK), got together to start a private equity hotel fund, which later became lodging REIT RLJ Lodging Trust.

You’ve got to be able to convince other people to go on that vision journey with you. That’s probably the most critical thing of being able to accumulate a number of business opportunities—you must be able to attract talented people who believe in your vision, who believe that you are willing to work as hard as they are. No business is an island. Every business must have people who share the goals, purpose, and culture to make it successful.

There are currently three Black CEOs of publicly traded REITs, two of whom were hired and advanced under your tutelage. How were you able to achieve that?

How you find those talented people is that you give them a belief that they have an opportunity to be as successful as they have the potential to be, in the environment that you offer them.

Unfortunately, many companies, most of those white companies, don’t allow Blacks into what I call the deal flow that determines who gets hired, who gets promoted, who gets placed in the top positions that can lead to either the top job as CEO or CFO, or other strategic executive positions. That’s because there’s a tendency to not believe in the Black workforce. Some people call it systemic racism, some people just call it fear. Other people could call it just plain, “We don’t want to take a risk on someone failing in our business.” If you’re not in the deal flow you don’t get the opportunity.

The NFL implemented the Rooney Rule in 2003, requiring all teams must interview at least one minority candidate when they are hiring a head coach. My version of the Rooney Rule in business is that before you hire someone you must interview at least three Black professionals. The same thing goes for minority-owned businesses—before you hire a business to do something, interview at least two minority-owned business. If they can do the job, give them the opportunity. If they can’t, put them in the queue for other opportunities that may come along.

One of the things I’m most proud of is that I have been successful in delivering three of the 14 Black CEOs to Wall Street, and two of them are female.

Right now there’s an intensifying drumbeat around the diversification of corporate boards. Why is that something CEOs should really welcome and accept?

First of all, it’s good business for CEOs to diversify their board because they get diversification of ideas—a diversification of understanding the changes in not only the business world but in the consumer world. If you’ve got Black Americans on your board, you get a voice on Black issues. Keep in mind, 70% of the U.S. economy comes out of the consumer’s pocket, and there are 40 million Black Americans.

Black Americans unfortunately have a wealth gap that’s about 10 times less than that of white people. This country can’t grow economically to the level that it should if it’s got a huge population on the sidelines.

To me, that’s why businesses should make sure that their board is represented by diverse groups. It starts out as good business, and ultimately it ends up being good for the country.

Nareit recently launched its Dividends Through Diversity, Equity & Inclusion (DDEI) CEO Council, representing every sector and subsector of the industry. Where do you think the council should focus its collective efforts?

Without accountability, goals in business tend to become empty in implementation. Because everyone’s responsible, no one’s responsible, so goals just get shunted to the side. To me, coming up with a charter without a mandate with an accountable requirement to the charter is a waste of time.

There are companies like Glass Lewis and ISS that evaluate corporations on their performance related to their charter. If you’ve got a compensation committee charter and they’re paying the executives without regard to certain criteria, they will recommend to some of the big stockholders in those companies, like Fidelity or BlackRock, a no vote. That will get the attention of the CEO and all the shareholders.

How has RLJ Lodging weathered the pandemic?

We were fortunate in that we had positioned ourselves before the pandemic on making sure we purchased the right hotels and managed the right hotels that fit with our strategy of serving the leisure and business traveler customers.

We wanted to make sure that our hotels were located in markets where we would find that customer flow, that airlift that brought customers for various business or leisure types of activities, or in markets where entry was difficult so we wouldn’t find ourself facing a lot of new build. We also focused on making sure our hotels were refreshed, renovated, and spending their capex in the right way to make the hotel comfortable and compliant with our strategy.

Of course, we focused on hiring a good management team and overseeing the management companies that were running our hotels. We did all those things, and we made sure that our financials and our balance sheet were structured to withstand the cycles, whether the normal cycles of the hotel industry or a cycle caused by an unintended event. When COVID struck, we had to close almost 50% of our properties because if a hotel’s not making money, there’s no sense of keeping it up.

Because we happened to sell off some properties and position ourselves to deal with our leverage and our capital, we were able to weather the financial consequences of COVID by having enough liquidity on hand, and having enough of a comfortable relationship with our banks to continue to have the liquidity to keep our hotels operating.

Turning to systemic racism and unconscious bias, how much should people of color conform to the cultures of their workplace, versus how much should their workplace conform to them?

If you feel that you’re doing what you feel is right in the workplace and what is consistent with the company’s culture, there’s no need to try to modify your lifestyle. If the company has a good culture, it will accept your differences.

You can’t walk into the office expecting to be treated differently, because if you do that, you’re going to be looking for divergence in the way you’re treated. That can cause you to have anxiety that’s not really justified, so you’ve got to be confident in yourself.

You will run into people in conditions that are just plain unfair, or to say it in a full sentence, racist. Under that circumstance, you have to confront it head on and make the case that you’re not prepared to be treated that way. If you are, you have one of two options: go to HR or legal, or, the ultimate remedy, you take your expertise elsewhere. The trick in this is how to manage it where you don’t feel like you’re selling your soul to get a job, or to keep it.

At the same time, if you’re going around looking for a certain behavior then that’s detrimental to your wellbeing on the job. That’s something that Black Americans have to live with. It’s something that many white Americans don’t understand. I know in my career, and you can probably talk to any Black man or woman in America, we have all encountered situations that are clearly based on indifference, ignorance, or just plain racism.

Now, you can take those three categories and say, “How do I deal with it?” Ignorance, you can work around. Indifference, you may be able to work around. Racism brings it squarely to you, and that’s when your self-esteem has to take over and say, “This is not something I’m going to tolerate.” The key question is: How do you calibrate when you encounter those things?

And finally, are you working on any new business ventures?

There’s one thing that I really want to accomplish: the implementation of auto-portability in the 401(k) space. Black Americans, when they leave a job, cash out their retirement savings accounts at approximately 60% to 70% compared to white Americans. That means not only do they pay taxes when they cash out on their 401(k) account, they also lose the savings for retirement.

My goal would be to put close to $1 billion, or more, back into the pockets of Black Americans over the next generation. It doesn’t require government legislation and it doesn’t require taxpayers to go in their pocket to do it. It’s just changing a behavior and getting those large corporations to say, “We want our Black employees and other low-wage workers to stop cashing out and put this money into savings.”

The other thing that I’m doing is looking at the biggest problem facing Black businesspeople—lack of access to capital. Without capital, you cannot create a business that gets to scale, and therefore you cannot compete. We’ve got to figure out a way to put money back into the pockets of Black Americans.

When Tom Baltimore and I bought our first six hotels, overnight we became the largest Black-owned hotel company in the country. We went out and raised capital in the private equity fund and then converted the private equity fund into a REIT. We were able to raise capital because of my connections and Tom’s management skills. That’s what made the difference as to why we are a hotel REIT—because we were able to get access to capital.

I’m asking the Treasury Department to implement a type of tax certificate program that would encourage minority ownership across all business types by saying that if a Black person creates a company and the company makes a profit, an investor can sell their shares or interest and get a reduction in their capital gains tax.

Paying It Forward

Thomas Baltimore, Jr., chairman, president, and CEO of Park Hotels & Resorts Inc. (NYSE: PK) and Leslie Hale, president and CEO of RLJ Lodging Trust (NYSE: RLJ), share their personal reflections on Robert Johnson as a mentor and colleague. Baltimore previously served as president and CEO of RLJ Lodging Trust. The REIT’s predecessor entity, RLJ Development, was co-founded by Baltimore and Johnson in 2000.

Tom Baltimore

I had no better mentor and business partner than Bob Johnson. Beginning at RLJ together and buying our first portfolio from Hilton back in 2001, subsequently launching and raising three private equity funds, merging the last two funds, and taking RLJ public—that was just an amazing journey. We spent nearly 17 years together in a very successful partnership, so I am eternally grateful for his support, for his confidence and mentoring, but also the incredible platform and the number of people that came alongside that.

It was an incredible journey that also provided great jobs and opportunities for many other people, particularly people of color who probably would not have had those opportunities otherwise.

He’s a brilliant entrepreneur, he’s curious, he’s thoughtful, he’s always thinking around corners and he’s willing to invest in people, especially people who are prepared to bet on themselves. One of the reasons that we were such great partners was that he was prepared to bet on me and support me because I was prepared to take the appropriate amount of risk and to bet on myself. He has probably been responsible for creating and supporting as many African American entrepreneurs as anybody.

I’m also grateful that after that 17-year journey, when I got a call to rejoin Hilton to spin out their portfolio into Park Hotels, Bob didn’t stand in my way. He knew that was the right growth opportunity for me. He also knew that I had built a team of men and women that were prepared to continue on with RLJ. That speaks to his enormous grace and understanding.

Leslie Hale

Bob is a visionary, he’s someone who’s able to see an opportunity where most people can’t. His ability to do that has given rise to a number of African American executives excelling in a range of industries. It is his ability to be able to figure out how to take something and monetize it that has been important not only to me but to many executives in the industries that he’s touched.

I’m also inspired by Bob’s ability to continuously pay it forward and to be able to look at people and see their talent. He sold BET [in 2000] and he could have easily just retired, but instead he sought to continue to invest in businesses. In so doing, he gave people of color the opportunity to function in leadership roles.

There are very few African American CEOs of publicly traded companies, and three of them are from his organizations. That speaks to him being a visionary, but it also speaks to his character in terms of investing and giving people a shot. I wouldn’t be where I am today without Bob Johnson.